Our attempt to travel by boat around the eastern U.S

We weren’t ready to turn east

So, we went to Alaska.

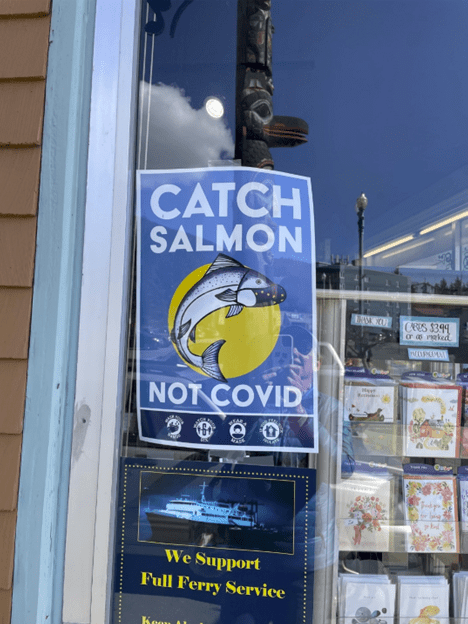

We were in Seattle and realized we would probably never be closer, so now was the time. We thought about driving, but the Covid rules for driving through Canada were still pretty strict. None of this trip has been about moving fast, so flying didn’t appeal either. We took the ferry.

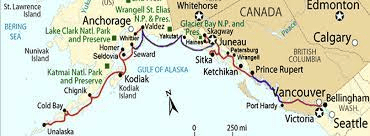

The Alaska Marine Highway System is not a highway, but a ferry system that covers 3,500 miles of coastal Alaska (for comparison, the continental US is 2,800 miles wide).

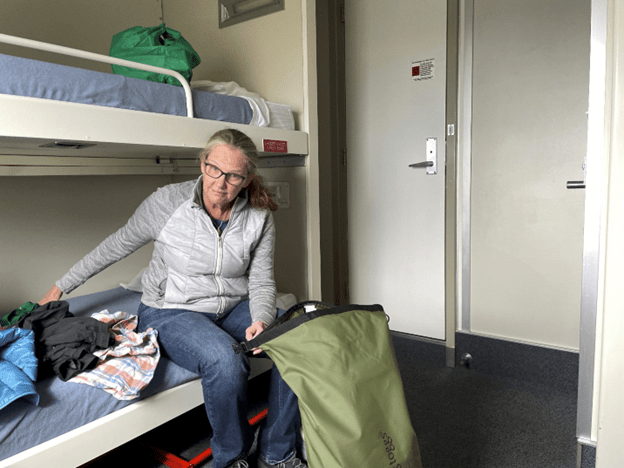

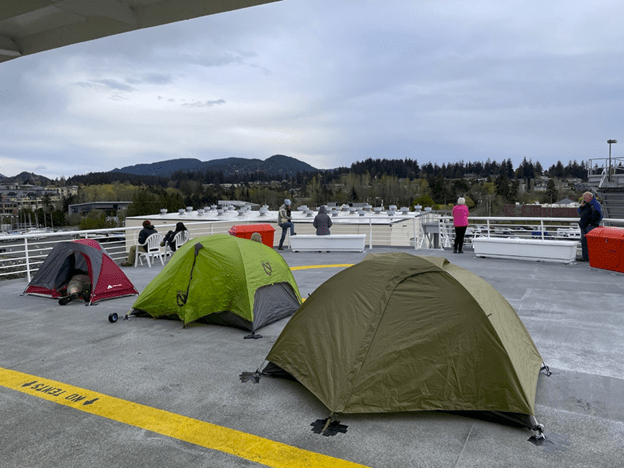

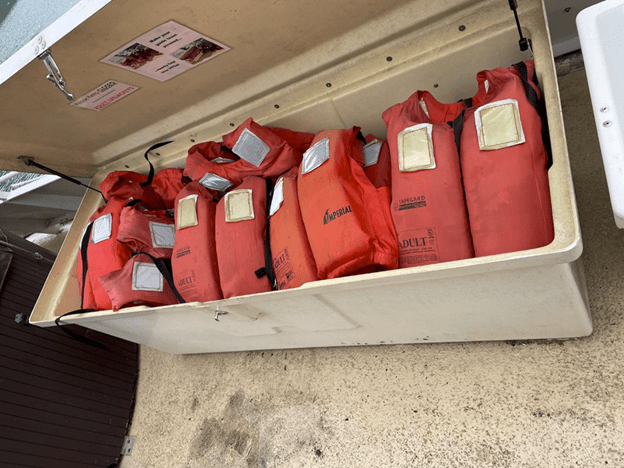

The ferries are old (our first ferry was built in 1963), basic and slow. We left out car behind and traveled as walk-ons. We rented a berth, but many people slept on the floor, in chairs or on tents taped down on the rear deck. There’s no cell phone coverage or wifi onboard, but sometimes as you pass a town, you have a few minutes to text your family.

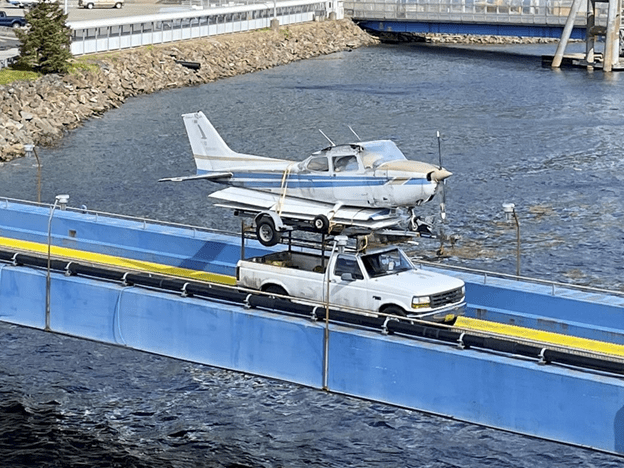

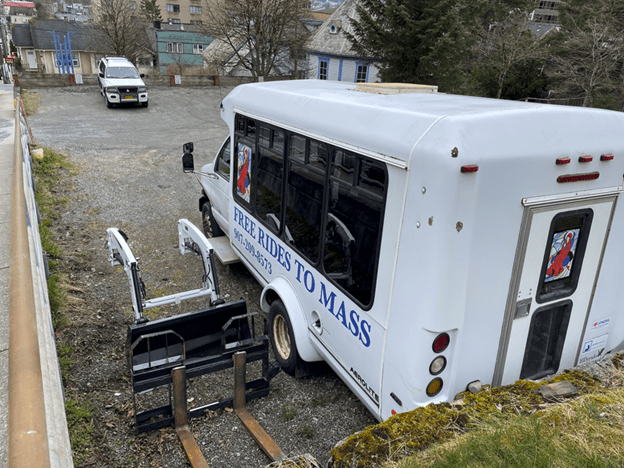

The ferry is a lifeline for coastal Alaska, many of the towns and even cities have no land access. Some towns are served weekly; others as seldomly as once a month. Because it was still mid-April, most of the people we met were not tourists. There were loads of younger people coming up for jobs for the summer tourist season, contractors coming up with supplies for the building season and people who had just decided to reinvent themselves in a new place. We found out later that the ferry is also how people get to and from college, how high school sports teams travel (they stay the weekend) and how things like firetrucks and even airplanes get delivered. We always got a positive reaction from locals when they found out how we had traveled. It was an instant connection.

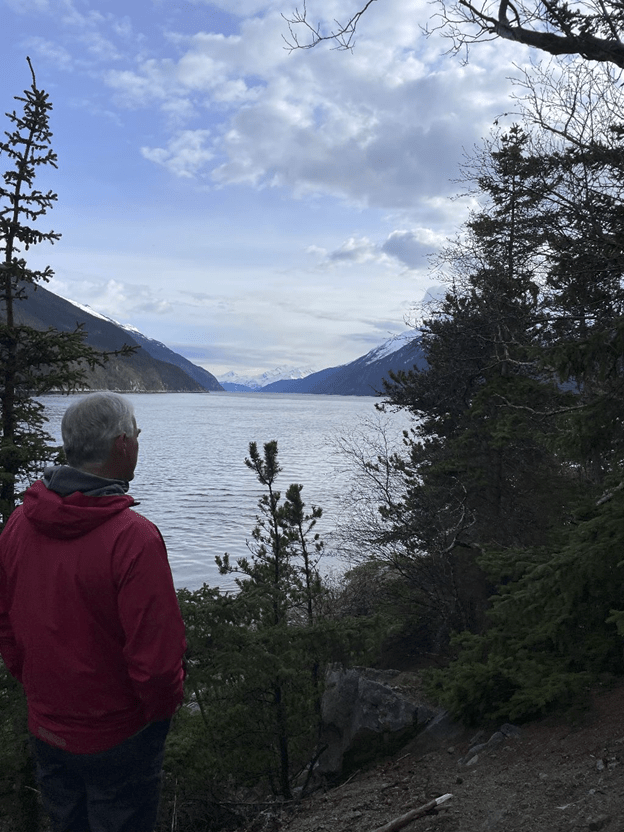

Southeast Alaska is gorgeous; we each took hundreds of pictures of mountains, waterfalls, wildlife, and glaciers. It is no wonder it’s such a popular cruising area. I was expecting the beauty; I was not expecting the feel of the place to be so different from any other state we have visited.

We arrived in Ketchikan early on a Friday morning (after two nights on the ferry). Ketchikan has no road access to the rest of the continent. Its thirty miles of road allow car travel throughout town, but that’s it. This isolation is part of what defines Alaska. Even Juneau, the capital, can only be reached by water or air. I suppose Hawaii must be something like this, but without the harsh, dark winter and the tens of thousands of acres of wilderness between population centers.

We met a traveling nurse who told us about how surprisingly grateful a family was when she agreed to come in to do a scan on their son on her day off. Her colleagues explained that if she had not come in the parents would have had to pay to fly him up to Juneau for this basic medical care.

Ketchikan, like most of the rest of the places we visited, is economically reeling after two summers without cruise ships. A number of stores/restaurants had gone out of business, many others were closed but you could see the owners inside busily unpacking boxes and stocking shelves. We were immediately identified as tourists – we were wearing jackets and not tank tops in the 45-ish degree weather. People were glad to see us – one guy even shook Jerry’s hand when we walked into a local bar, “Welcome to Ketchikan!”

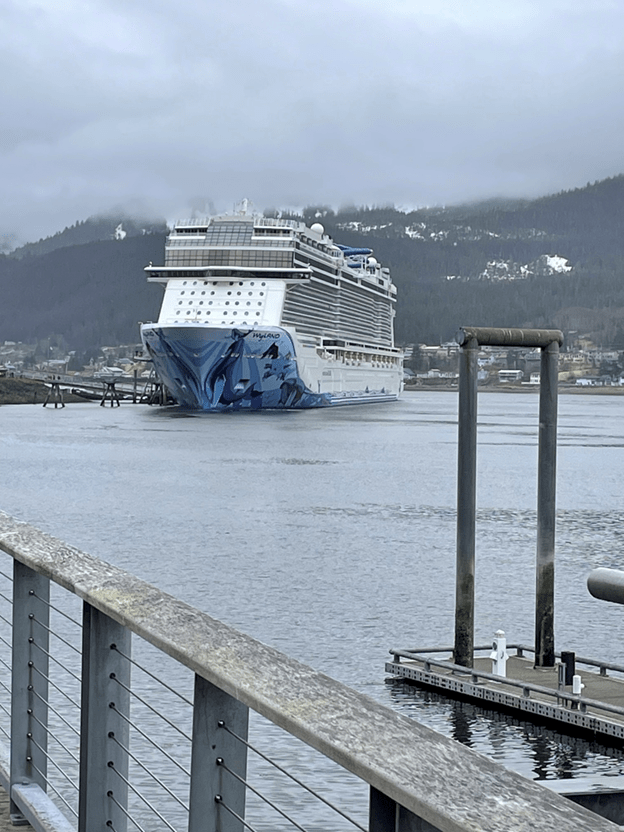

We learned immediately that the summer revolves around the big cruise ships. Everyone knew that the first ship was coming in on April 28th – sort of like everyone knows that Christmas is on the 25th of December. We learned later that all store owners are given a schedule of ships and their expected number of passengers. This document defines life from early May until late October.

Before we left Seattle we had booked a last minute cruise ourselves. A big cruise has never appealed to us, but luckily we found Uncruise, a small boat cruise company that specializes in adventure travel.

We spent a week traveling through fjords and up to glaciers between Ketchikan and Juneau. We went kayaking off the back of the ship, got dropped off in inflatable boats to hike and even got to bushwhack. Because we were there before cruise season (apparently our boat was too small to be included on the cruise schedule), we had the beauty to ourselves.

The captain would alter course or stop when he saw something he thought we would like to see, like mountain goats or whales. It was wonderful. The cruise also reminded us that we are not unique. The thirty passengers were all about our age (apparently the mix changes later in the season) and experienced paddlers and hikers. We sat at dinner one night with a couple – she had worked for forty years at the same company (vs me at thirty-six) and he had worked in IT and was now working on encouraging biking and walking solutions (Jerry exactly).

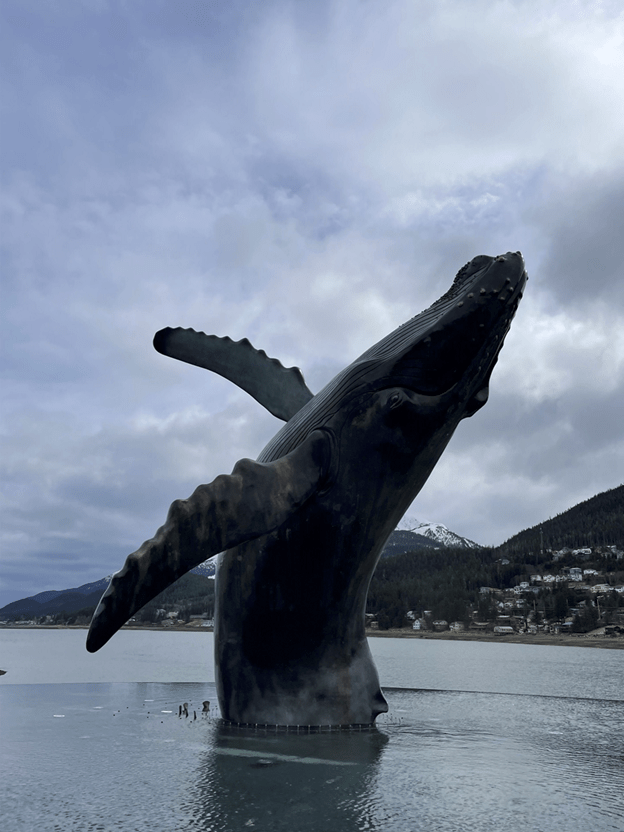

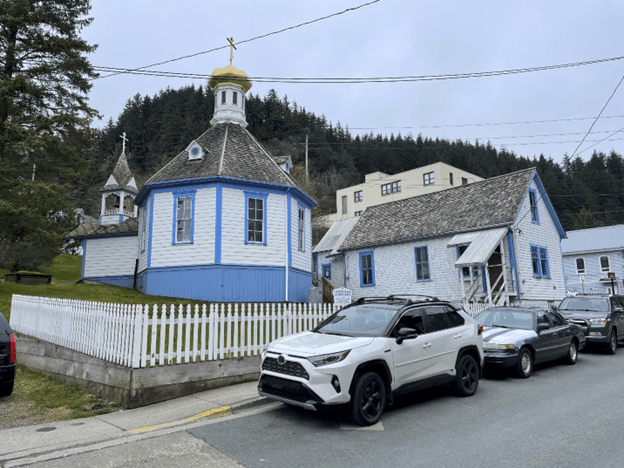

After the cruise, we spent a couple of days in Juneau, watched the first cruise ship come in, walked all over town including up to the Russian Orthodox church. Early Russian influence was evident all-over southeastern Alaska, not just in churches but in the nesting dolls that seemed to be for sale everywhere. Juneau was the only place that we saw anybody even close to dressed up (the jeans, hiking boats and flannel shirt look was one of my favorite things about being in Alaska!) – and they were headed into the state capital building.

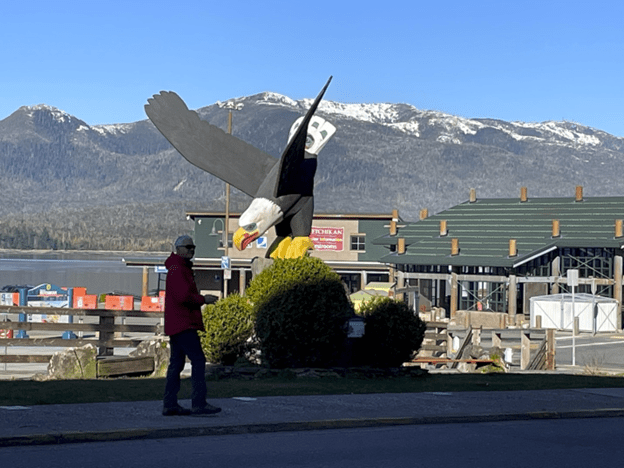

In Juneau, as in Ketchikan and Wrangell (where we spent a cruise afternoon looking at petroglyphs on a beach), the native Alaskan presence is integral to the city. In addition to totem poles and Alaskan inspired graphics, there were museums and active cultural centers. Educational plaques and exhibits reinforced how horrifically native Alaskans were treated and explained how efforts are still be made to revive critical cultural elements, including the language.

Everywhere we went in southeast Alaska, there was an almost overwhelming presence of ravens and eagles. It made sense then that these are the names of the two Tlingit moieties (there are clan divisions below this). The Tlingits are a matrilineal society, and when they marry (traditionally, Eagle only marries Raven and vice versa), the children become part of the mother’s group.

Traditionally, once Tlingit children reached a certain young age (it varied by clan) they were raised by aunt and uncles. This ended with our parents’ generation, who kept our generation with them. Once when a bunch of middle school age native kids rode by on their bikes, they spotted a young couple and started calling out, “Hi, Auntie, have a great day, I love you!” I can’t imagine the kids I know doing this in front of their friends, but it seems the aunt/uncle relationship is still a significant one.

After Juneau, we traveled (again by ferry) to Skagway, the northern most city in the Inside Passage, where we stayed for several days. Skagway was the take-off point for the Klondike Gold Rush and they do a good job of explaining just how brutal the time was. The town is tiny, four roads wide by 23 cross streets long (less than a mile). It is again a tourist town and an expensive place to live. (We paid $9 for a loaf of prepackaged sliced bread.) Apparently, there are about 1000 permanent residents, but a few hundred of them leave in the winter to find cheap places to stay in southeast Asia. Because tourist season is so busy; it is in the winter that people take classes, have local festivals and socialize.

We have traveled a lot over the years, but although I been disappointed that vacations were ending and that there were still things we hadn’t seen, I have never been truly sad to leave somewhere as I was when we got back on the ferry for our three day trip home. We actually sat in our AirBNB the last evening studying the ferry schedule, trying to figure out if there was somewhere we could go to extend our time.

John Muir said, “you should never go to Alaska as a young man because you’ll never be satisfied with any other place as long as you live.” I think he was right.

Slow Driving

April 30, 2022

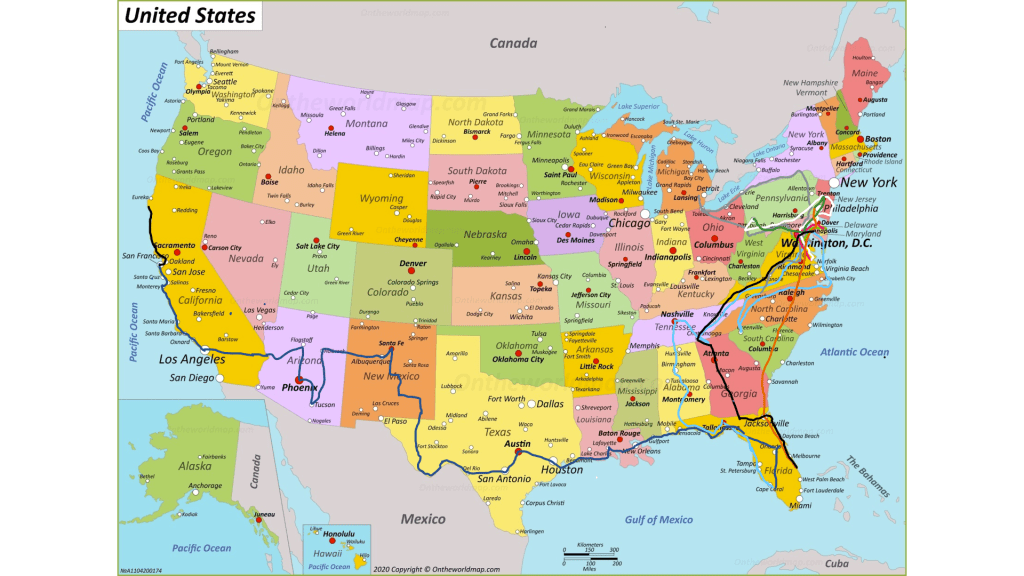

You can drive from Sanibel, FL to Los Angeles, CA in forty hours. We took 48 days.

As you might have guessed, we are taking the scenic route. This means staying off the interstates (less than 100 miles so far), sticking to US highways, state roads and our new favorite, farm to market roads (exactly what they sound like). We don’t drive every day and we don’t drive for very long. Our shortest day, between Sequim and Port Townsend, Washington was 30 miles. Our usual limit is about three hours.

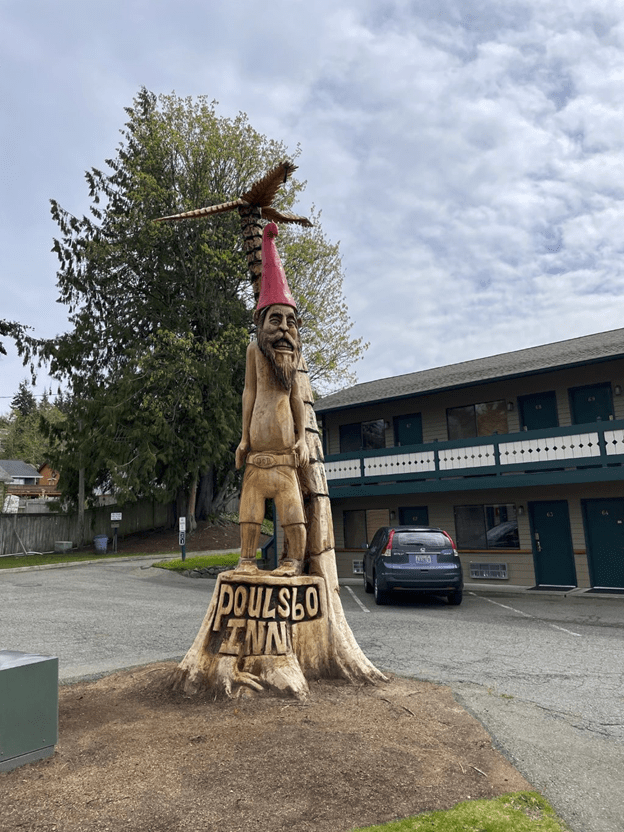

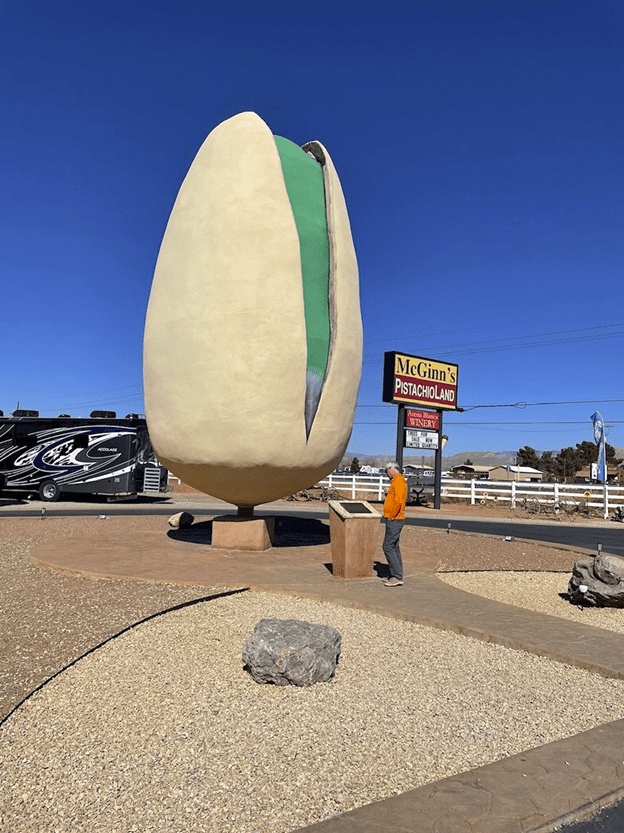

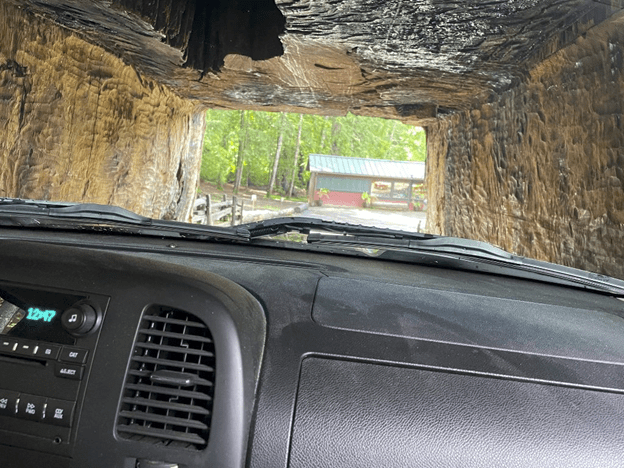

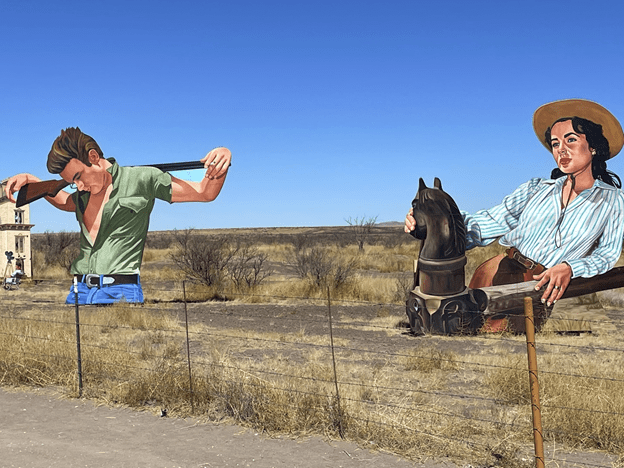

Unlike the monotonous interstates, outside of metropolitan areas, the US Highways are lovely – hugging the shoreline, forming the Main Street of small towns, winding through forests and pastureland. Because they were once the only way to travel cross country, they were once lined with odd roadside attractions, one-of-a-kind restaurants and small quirky motels. Some of these are still around.

I have always been kind of a snob about stopping at “tourist traps” and felt they were kind of ridiculous, but I have gained a new appreciation for people’s marketing creativity, not to mention the chance for a clean bathroom and a cold drink.

This trip is just so much fun. I can’t wait to find out what we discover on the trip back east!

Beauty and Fear on The PCH

California 1 aka the Pacific Coast Highway (PCH) is known as one of America’s most beautiful drives. And it is stunning.

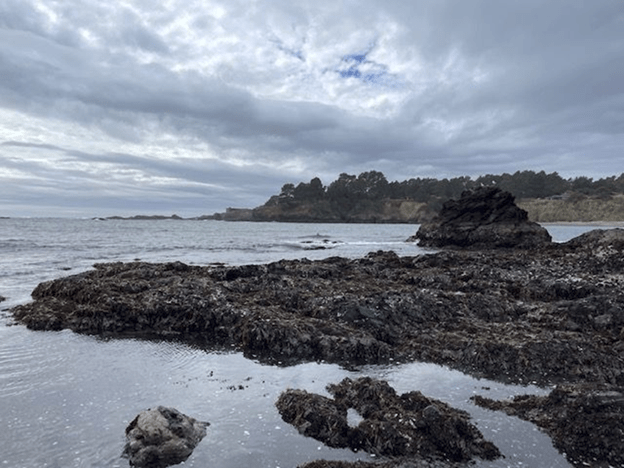

For those of us who grew up on the east coast, we know that (except maybe in Maine) the ocean sits where it properly should, at the far edge of a coastal plain. As you approach, the land becomes increasingly flatter and sandier until you reach the sea. The Pacific is starkly different. The ocean comes right up to the edge of the mountains, with huge boulders tossed haphazardly into the surf. The force of huge waves crashing over these rocks, with water and spray tossed high into the air creates a dramatic scene unknown on the eastern shores.

The PCH, somewhat magically carved into the mountains along the coast, alternates between small coastal villages and narrow winding roads hugging the side of cliff faces high above the waves. Guard rails are used sparingly. For me traveling this route meant spending several hours every day afraid.

I don’t know when my fear of heights of started, but generally it is pretty easy to manage. On hikes, I decline to climb the watch tower steps, foregoing the view in order to “rest.” When I couldn’t avoid going to the top of the Eiffel tower, I stood with my back pressed against the wall next to the elevator while others walked to the edge. In glass elevators, I turn and face the door.

Despite this, I was enthusiastic about traveling this highway. (Did I mention “stunning” and small coastal villages?) But it meant I was almost constantly in flight or fight mode, with an accelerated heart rate and somewhat rapid breathing. I realized at one point that I had one hand on my seatbelt button and one on the door handle as if I would leap out of the car as we inevitably plunged over the cliff.

I think it is impossible for others who have not experienced some form of anxiety, no matter how sympathetic, to understand. Your brain knows it is ridiculous – the tires will continue to hug the road, your husband will not suddenly decide to ignore a curve. But your body is telling your brain that it is wrong and that you in imminent danger. “Some irrational fear had taken over my body…that voice of reason had been shoved into a corner at the back of my brain. Another voice was in control now.” (Eva Holland)

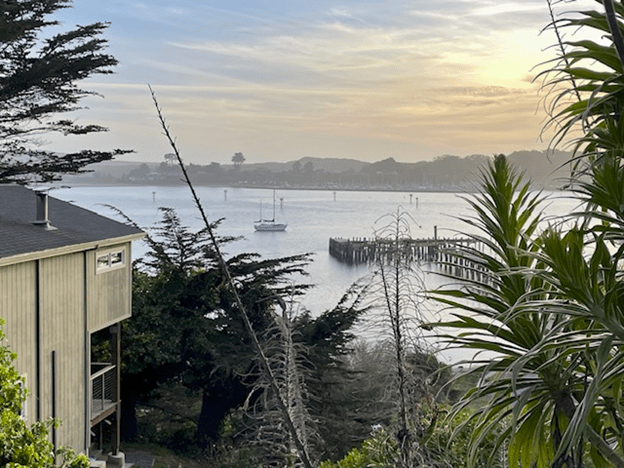

Each night we would find a coastal town to stay in. Unlike the Chesapeake, where overfishing has almost destroyed the industry, there were active fishing fleets, hordes of sea lions and seals lying on rocks and piers, beautiful ocean views, tiny local restaurants and beach walks amongst the rocks and tidal pools.

And every night I would do some research on acrophobia. (It started when I was wondering if CBD gummies would calm me down. Unclear.) I learned that I do not in fact have acrophobia but have self-diagnosed myself with “stimulus dependent visual height intolerance.” In short, I am afraid of edges.

“Fear of edges is not a fear of heights. I don’t mind being up high at all. Planes, elevators, skyscrapers, none of those bother me. It is standing at the edge and being confronted with an unreasonable belief that I am going to tip over and something horrible will happen, the unknown something, or that I will be left on that edge forever, unable to move, paralyzed for eternity.” (Patty White)

The PCH is by its nature mile upon mile of edges. If we had been driving in the recommended north to south route, where you hug the rim, I simply would not have been able to proceed. That being said, if you have the chance, drive the Pacific Coast Highway. (I recommend south to north.) And take your time, stopping to enjoy the view from the lookouts, the lighthouses, the coastal towns and the sheer beauty of the coast. It’s worth it.

Ten things we learned while traveling

March 13, 2022

- A blind man can change your tires.

2.There’s an official definition of a honky tonk.

3. Southern accents are disappearing (being called “you guys” in Birmingham, AL is just wrong!).

4. Cars don’t rust in the west, so there are a lot of old ones.

5. If there are out of place items on a menu (perogies in a wine bar, homemade samosas in a convenience store) they are the cook’s specialty and you should order them.

6. Using a wash and fold service at the laundromat is an affordable but surprisingly satisfying luxury.

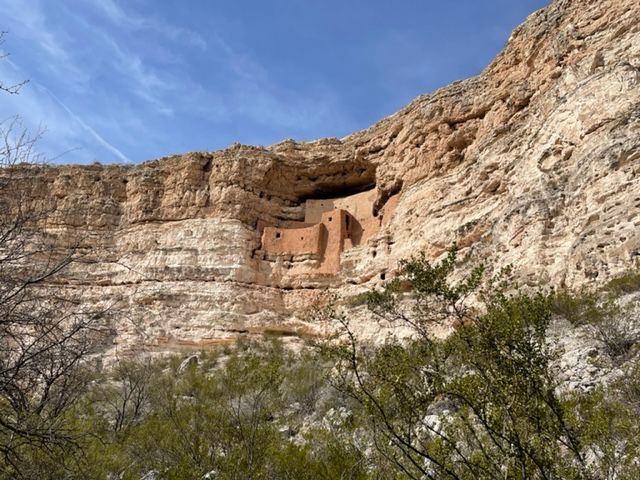

7. National parks are a national treasure, especially in the off season.

8. The difference between Mexican and Tex-Mex/New Mexican food.

9. The desert is brutal, even in winter. I totally get it now why people leave water out for people crossing the border illegally.

10. You can be so far out in the middle of nowhere that ranchers driving on their own property messes up the Google maps algorithm.

____________

Not our plan..

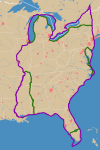

Last year we bought a used boat to start the adventure of a lifetime, traveling America’s Great Loop – a year-ish long trip from Chesapeake Bay to New York Harbor through the Erie Canal, looping Michigan on the Great Lakes, down a bunch of rivers to the Gulf of Mexico, around Florida and back up the east coast.

We knew our boat needed some work. We did NOT know that we should not trust our mechanic. After several adventures and headaches, we got our boat to the extremely busy best boatyard on the Chesapeake Bay on Labor Day. With our house occupied (house sitters) and no loose ends left at home, we decided to take off on a road trip and come back as soon as the boat was ready. We thought we’d be gone about three weeks. We’re still driving.

As you can see above, we are now doing a different loop. And boy, is it fun!